A Deconstruction

If you haven’t yet seen the first part of Peter Jackson’s new trilogy based on the esteemed fantasy novel/children’s book by J. R. R. Tolkien and don’t wish to have it tainted by misanthropic grumblings and general pedantry, stop here. There are some very strong and mixed feelings bubbling up within me as I write this and many of them carry with them spoilers.

In fact, just in case someone’s stumbled across this blog in search of nothing more than a simple précis and an everyman’s star rating, WARNING: HERE BE SPOILERS. Further warning:. This review is long and rambling and relies to an extent on your having seen The Lord of the Rings trilogy. That said, let’s start at the beginning: “In a hole in the group there lived a hobbit…”

The film opens in familiar surroundings, Bag End, on a familiar occasion, the build-up to Bilbo Baggins’ long-expected party. Bilbo, played by a returning Ian Holm, is adding the final touches to his memoirs as he considers at last leaving is home in The Shire and heading for distant, unknown climes.

Elijah Wood returns in a brief cameo as Frodo Baggins, the erstwhile hero of The Lord of the Rings. They discuss the Sackville-Baggins’ and their pilfering ways, the imminent appearance of Gandalf (back in grey) and his marvelous fireworks; we even get to see Frodo put up a recognizable sign that reads ‘No Admittance Except on Party Business’. So far, so comfortable, if a little derivative. From the off, there’s the sense that the film is playing it safe, treading water even. Unfortunately, this is not a feeling that goes away any time soon.

Pretty quickly, we’re into the flashback that makes up the rest of the story, namely Bilbo’s first unexpected journey that took him away from his home in The Shire, across the length of Middle Earth, into unimaginable danger, before, as well you know, depositing him back where he began. If that also sounds familiar, it’s because the plot of ‘The Hobbit’, or There And Back Again, as a work of literature bears many similarities to its successor.

Bilbo Baggins, now played as a staid, conservative figure by Martin Freeman (Sherlock, The Hitchhiker’s Guide…), is approached by Gandalf, the ever-reliable, twinkly-eyed Sir Ian McKellen, who makes him an offer of adventure that Bilbo is quick to refuse. The Refusal of The Call dealt with, Bilbo nevertheless finds himself drawn into Gandalf’s quest as one by one, then all at once, a band of dwarves make their appearance on his doorstep.

This prolonged sequence is played mostly for laughs with a series of evidently un-house-trained strangers appearing on Bilbo’s doorstep and proceeding to make themselves at home, to the increasing exasperation of their host. They quickly upset his orderly home – raiding the larder and juggling the crockery. It’s unsubstantial stuff, but entertaining, and a reasonably effective way of introducing us to Thorin’s band of dwarves, of whom there are twelve. Twelve!

These are, in no particular order, the moody but noble Thorin (Richard Armitage, Spooks); the thuggish Dwalin (Graham MacTavish, Rambo); the scholarly Balin (Ken Stott, Hancock and Joan); brash twins Fíli and Kíli (Dean O’Gorman, Young Hercules, and Aidan Turner, Being Human); Ori, the youngest of the group (Adam Brown, ChuckleVision); Dori, who’s a little bit fat (Mark Hadlow, King Kong); Nori, who has braids (District 9); Bifur, who’s got an axe in his head (William Kircher, Shark in the Park); the jovial Bofur (James Nesbitt, Jekyll); Bombur, who’s very fat (Stephen Hunter, Ladies Night); Óin, who’s a bit deaf (John Callen, Worzel Gummidge Down Under); and Glóin, who's distinguished only in that he seemingly has no distinguishing features whatsoever (Peter Hambleton, The Rainbow Warrior).

These are mostly character actors who’ve worked with Jackson before in some capacity (with a few notable exceptions, such as Armitage, Nesbitt, MacTavish, etc.) and if they sound like they’re difficult to keep track of, don’t worry: most of them have little or no part to play in the story. Several of the dwarves, I could swear, have no lines at all, and, by the end of the film’s quest, could reasonably be mistaken for the most persistent extras of all time. When Bilbo declares, “There are too many dwarves in my dining room as it is”, an otherwise good line, the film has no idea how prescient its being.

Furthermore, it’s about the point the dwarves begin performing a truncated version of, let’s call it, The Crockery Song – “Chip the glasses and crack the plates! / Blunt the knives and bend the forks! / That's what Bilbo Baggins hates—” – that it becomes clear how much of the story is still just padding. It was here that my heart sank as I came to the realisation that either An Unexpected Journey was going to turn out to be a) a kid’s film, or b) utterly tonally inconsistent. Though there’s nothing in there that would upset a precocious ten-year old, I believe the latter to be more the case.

By the time the ragtag band finally leave on their quest to reclaim the Lonely Mountain from Smaug the Dragon almost an hour has passed. The film up until this point has been slow and exploratory – in all fairness, fan-ish. I was cynical when New Line announced their intention to turn the relatively slim tome The Hobbit into not two but three feature-length films, but felt, rightfully enough, there was enough material in the expanded universe to make up for the deficit.

For instance, Radagast the Brown, one of Gandalf’s order of wizards (played by Sylvester McCoy of Doctor Who fame) makes an non-canonical appearance. A twitchy, forgetful animal lover who barges into the film long enough to announce the re-emergence of an ancient evil in Mirkwood Forest before disappearing on his rabbit-drawn sleigh, Radagast’s presence is very much fan service, serving only to introduce a secondary plot involving the mysterious but oh-so familiar Necromancer, whose role will presumably be expanded upon in the later films.

However, this is when put in context much of a muchness. It all seems entirely episodic. For instance, the scene between Bilbo and the trolls, which does appear in the book, takes place over almost ten minutes – consisting mostly of some japery, some trickery, and some troll snot (instantly reminiscent of the second Harry Potter film), manages to feel overlong whilst simultaneously cutting Gandalf’s clever use of ventriloquism that is supposed to have distracted the trolls long enough for the sun to rise and turn them all to stone. The Tolkien fan in me cried out for purism; the casual filmgoer in me was very nearly bored.

I know that it’s perhaps unfair to judge An Unexpected Journey in the context of the book and the three film sequels, but it’s almost unavoidable. Gandalf’s swooping in out of nowhere to save the day is one of two occasions he does so in the film – a Gandalf ex machine, if you will. To it’s credit certainly makes me want to go back and reread the book more than Lord of the Rings did – which in terms of getting kids into literature is no bad thing – but not for the reasons I’d hoped.

Still, An Unexpected Journey, odd, flawed, and strangely paced as it may be, was nevertheless occasionally quite engrossing. The flashback sequence that opens the film, narrated by Holm’s Bilbo, which tells the tale of how Smaug came to the mountain, was a lovely sequence which, though not featured in the book, set up neatly how the dwarves came to leave Erebor, the Lonely Mountain, and how Thorin’s obsession to reclaim it came about. It draws on the fall of Sauron from The Fellowship of the Ring and represents, along with another later flashback, a brief return to the epicness – in the terms of scale and ambition – that Lord of the Rings achieved so masterfully. To return inevitably to the flipside, it’s a shame that the cast was, on the whole, handled so poorly, not to mention certain aspects of the CGI, and that other such uses of material from the Appendices were fitted into the narrative somewhat less engrossingly.

To handle these complains in order, despite attempts to establish Thorin Oakenshield as a well-rounded character – in mourning for his homeland and longing to revenge his father’s death – the film is not entirely successful in doing so. The fact remains that Thorin ultimately longs not so much for the mountain and the community it represents than for the gold and promise of wealth it contains. As for the death of his father, the failure to connect with that may lie partly on the shoulders of Azog, his father’s killer, whom I will return to later.

It’s even more galling when comparing Thorin with a character such as Aragorn: Aragorn who similarly longs to sit on the throne of Gondor and comes from a broken line of kings, but whose quest is grounded in his fear of failure and the curse of Isildur that haunts him. Again, call it a failure of Tolkien’s writing if you must, heretical though that may seen, but Thorin cannot scale the same heights, even with an actor as deeply charismatic as Armitage straining to achieve credibility. The dwarves, forgettable individually, also fail to work as a whole due to lack of differentiation between them: the reason the Fellowship worked dramatically is that it contained a full range of characters, from the seemingly aloof elf to the outgoing dwarf, by way of a number of well-differentiated hobbits.

Bilbo, who otherwise perhaps most resembles Samwise Gamgee in terms of characters, goes some way towards remedying this, with Freeman turning it a restrained but remarkably likeable performance. There’s no earnest Frodo to balance him out, however, no trouble-causing Merry and Pippen – both with their own arcs – or angst-ridden Boromir – with his own agenda. In short, there’s little or no dramatic tension. Thorin doesn’t think Bilbo belongs in the group and Bilbo agrees with him. Even Gandalf is left with relatively little to do.

When – and again, if you haven’t already got this, spoilers – he kills the grotesque Great Goblin (played by Barry Humphries, better known as Dame Edna Everage), the villain of the second act, the moment’s played for humour. “That’ll do it”, the many-chinned tyrant gurgles as Gandalf easily dispatches him. Coming where it does in the film, once can’t help but think back to the dramatic highpoint of Gandalf v. The Balrog in Fellowship. That, for want of a better word, was “serious”, that had consequences. In contrast, An Unexpected Journey seems content to coast along on charm, of which it has a sufficiency.

At around the halfway point of the film, the troupe arrives at Rivendell where Gandalf has designed to bring them for his own secret reasons. While the dwarves mess around, falling off chairs and juggling food, Gandalf conducts a private council with Elrond (Hugo Weaving), Galadriel (Cate Blanchett), and – surprise, surprise – Saruman the White (Christopher Lee). Let’s hope they don’t cut Saruman’s closure out of the third Hobbit film, There And Back Again, eh. And there arises a crucial concept: closure.

A meeting between four of the most powerful and awe-inspiring figures in all of Middle Earth should be fascinating: there are thousands of years of history between them, back-story that fills entire tomes. And there’s the problem: it’s been confined to the Appendices because it does not translate well dramatically. Even in the knowledge of the threat the Necromancer will later become, it’s hard to care. We already know what the payoff is, we’ve already seen it: we know how this story ends because we’ve already seen it in The Lord of the Rings trilogy. The magisterial Elrond; the radiant Galadriel; the mighty Saruman; Gandalf – it’s still just a group of people around a table laying out the plot. This isn’t the Star Wars prequels telling the story of events crucial to the following films – the rise and fall of a hero-villain. This is the story – spoilers, spoilers, spoilers – of how Sauron moved house, and, sadder still, Christopher Lee is looking old and tired indeed.

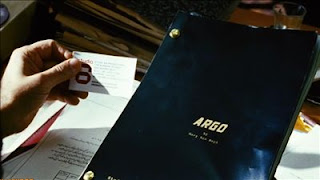

An Unexpected Journey feels like you’re almost always in the interim, waiting for something significant to happen. There’s no gravitas to it. The action-y bits feel like fluff and the talk-y bit are leaden. The purists will hate the former, the casual cinemagoer the latter. It all feels like a caper – based on it’s use in my review of the film Argo and, to an extent, of Seven Psychopaths, I’m beginning to hate that word – where things just intermittently stop. That’s part of the tonal problem.

A scene between Azog – getting to him shortly – and his orc band takes place at Weathertop, the hilltop ruins where the Ringwraiths attacked the Fellowship and wounded Frodo in the first of the LotR trilogy (from now on I’ll abridge it, as much for your sake as for mine). The scene itself is a standard villain-kills-subordinate-to-prove-his-ruthlessness – we get it, they’re orcs – and the set dressing just serves to try and imbue it with some non-existent significance. Action, exposition, and fan service mix like oil, water, and, I dunno, something that doesn’t go well with either of them, fire. New Zealand is, as always, very beautiful and goes some way towards making up for this. Somewhat.

It’s all small potatoes, minor jeopardy disguised as life or death. It all feels throwaway. A scene involving Thorin’s band on a cliff face directly mirrors a similar scene from Fellowship, down to someone screaming for them to take shelter (albeit with giant, boxing rock people standing in for an avalanche). An Unexpected Journey could lose an hour of runtime and not dispense with much of import. I’ve seen the whole extended LotR trilogy back to back, which stands at almost twelve hours, and felt exhausted but satisfied at the end of it; I never felt the same way here. In fact, it’s got me wanting to rewatch the sequels to see if it still holds up – and, again, not for reasons I’m entirely happy with.

Still, there are some very nice smaller moments, moments of pathos, such as when Gandalf explains to Galadriel why he chose Bilbo to join their party. The ethos he expresses, that of the importance of the little people, of everyday deeds, resonates beautifully with the films that have come before, with the inspiration behind Tolkien’s work – that of ordinary people in the trenches of World War I, fighting to make a difference.

To continue with the positives: Gollum. Just… Gollum. Riddles in the Dark. Gollum: brutal, threatening, jubilant, mad, pitiful Gollum. Serkis is as good in the role as ever and An Unexpected Journey gives a wonderful if self-contained showcase for his talents when Bilbo comes across the conflicted creature in the depths of the Misty Mountains. Serkis utterly redeems a whole swathe of the film merely through his presence. They even gave him his coracle.

What could otherwise have been a static interaction between Bilbo and Gollum is played wonderfully: Gollum creeps about in the dark, through the nooks and crannies of the cave in which he dwells, looking to strike, as Bilbo, sword drawn, tries to keep him at bay with a game of riddles. It may have been my note-taking that distracted me at the vital moment – mea culpa – but Bilbo’s discovery of the ring is a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it occurrence. Even so, Gollum’s dawning realization of exactly what the hobbit has in its pockets is terrifying. He nevertheless remains a sympathetic figure, or at least half one, for yes, indeed, Smeagol is present and accounted for, and in a particular instant Bilbo makes a decision – which I won’t reveal here, but which you can guess at – that resonates through all of Middle Earth, and it’s moment of consequence well earned.

All too soon, we leave Gollum behind in the caves of the Misty Mountains – “Bagginses! We hates it forever!” – knowing that, unless Jackson hugely changes up the plot of The Hobbit, we may never see him again. He will be missed.

The CGI success story that is Gollum serves to throw into harsh relief the film’s numerous other failures in that department. The orcs, previously just actors in make-up, have now been augmented with CGI, to varying degrees of— Azog. Azog, ostensibly the main villain of An Unexpected Journey, looks like a shaved albino baboon. Lurtz in, again – my apologies – Fellowship was a believably terrifying foe because he carried with him a physical realism. I didn’t even realize that Azog had a real-life actor behind his CGI visage – one Manu Bennett to Lurtz’s Lawrence Makoare, both presumably Maoris.

Even at the standard 24 frames per second, as opposed to the 48fps at which An Unexpected Journey was shot and will be playing as in certain cinemas, it was enough to complete rob Azog of any believability, thus diminishing my investment in Thorin taking his vengeance upon the character. The wargs, too, have changed – they no longer seem to carry the weight they once did. Everything is glossier, smoother somehow. In short, it’s lost its edge. To really push the boat out, this is one of the same criticisms levelled at the Star Wars prequels.

At this point my notes slip into stream of consciousness as the denouement approaches. I will try to recreate accurately as a representation of the emotional rollercoaster that was my state of mind at this point in the film (S.P.O.I.L.E.R.S:

- · Oh, look, the trees on fire. It’s like that bit from the song all the way back in Hobbiton – “The trees like torches blazed with light”. That’s sort of nice.

- · Ian McKellen’s whispering to a moth. That’s a call back to Lord of the Rings, which means the eagles are en route to save everyone. Duh. Damnit, now I’m getting annoyed with LotR over that plot hole about why they didn’t just get the eagles to drop the ring in Mount Doom for them if they’re at Gandalf’s beck and call. Damnit. Prequels should not retroactively make the sequels seem worsel.

- · Azog still looks like a hairless albino chimp, even more so by firelight. *sigh* I miss Lurtz.

- · I just realised I’m okay with waiting till next year to see the next one of these. That’s a bad sign.

- · This is a three star film.

- · The warg’s have cat’s-eyes. That sort of makes sense. But in this context, it just looks like a lot of miniature lens flares. It’s like their eyes are being directed by JJ Abrams.

- The quite-fat dwarf is about to die. I don’t care. That’s tragic in it’s own way. This is depressing.

- · This Azog/Thorin fight is surprisingly good. If they cut An Unexpected Journey down for the director’s version, there might actually be a very good film in here.

- · This is possibly a four star film.

- · Now the warg is eating him. It looks like he’s being chewed by something out of the back catalogue of a not very good taxidermist.

- · And the eagles are here just in time. That’s four out of the five armies from The Battles of the Five Armies we’ve seen so far.

- · And Azog is still alive. Of course. No resolution. He has to kark it at the end of the third film. I don’t care. I’m not invested enough to care.

- · An eagle grips the possibly dead hero in its claws as sad/dramatic music plays over. Great, now they’re ripping off the end of The Return of The King.

- · New Zealand is still very lovely.

- · I reckon if this wasn’t directed by the same guy who did LotR, the reviews would’ve been far less kind.

·

·

- Sir Ian carries the scene, even being shot on a separate set can’t hold this guy back.

- · Thorin is suddenly okay with Bilbo being part of the group after his sudden last minute display of courage. Wow, this is the emotional closure I’ve been waiting for… It feels sorta forced… Right, the films have to stand alone, too. That explains it.

- · And the f**king eagles drop them off on a plateau in the middle of nowhere. That would be too easy. There’s still Mirkwood to go.

- · In Fellowship, they would have made it at least partway through Mirkwood. The pacing here sucks. Guess which malevolent force is going to provide a second act diversion to The Desolation of Smaug?

- · At least we can now see Erebor on the horizon.

- · Bilbo: “The worst is behind us.” Irony aside, I fucking hope so.

- · A thrush bangs a snail on the side of the mountain. The echo travels through the halls of The Lonely Mountain. Something stirs beneath the golden hoard. A reptilian eye opens. Great, I’m now inexplicably excited about the next film. F**k you, Peter Jackson!

FURTHER NOTE: On the car journey back, my friend Josh argued that it’s the lack of human beings that make An Unexpected Journey disappointed: there’s no Aragorn or Boromir to relate to, no flawed human figures to identify with, and that these issues are inherent in the book, too. What do you expect when you attempt to make not just one two hour and forty minute film out of a three hundred page book (six paragraphs of truncated synopsis on Wikipedia)?*

*Or words to this effect

VERDICT: An Unexpected Journey is three parts LotR to one part Eragon. Its shows the occasional frustrating sign of being very good, but it isn’t, really. If my review leans heavily towards the negative – which I know it does – that’s only because of how frustrating the film is given the comparatively awesome three that have preceded it. I enjoyed it a fair bit while I was watching it, but given the source material and crew involved I’d hoped for more. While I can’t unreservedly say it’s good to be back in Middle Earth, An Unexpected Journey is never boring for too long and there’s some great stuff in there. The worst you can accuse it of is a lack of ambition. Still, it’s nice to catch up with some old friends and hopefully the new ones will grow into place over the next two films.

CAVEAT: As you might have guessed, I am hugely ambivalent about The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, perhaps more so than any other film I have ever seen. The weight of expectation on it was enormous - I wanted to love it - and I’m not entirely sure how to feel about it yet. This review may prove overly harsh or it may well be validated. These are still just my first impressions – I’m still working through them. For now though, it seems a bit – pardon my inexact metaphor – Looney Tunes meets The Hero with a Thousand Faces. I may come to re-evaluate. I genuinely hope so.